He was born in 1897, in the interior of the northeastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco.

It is harsh country with little water and much cactus, brilliantly described by the great Brazilian writer, Euclydes da Cunha, in his classic work Os Sertoes (The Backlands).

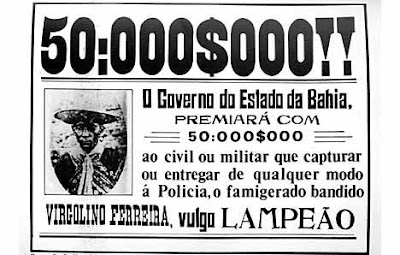

It was a time and a place of nicknames. Almost everyone had one. His was Lampião ( lampost) probably because he was so tall and thin. It was sometimes spelled Lampeão. The members of his gang called him Captain Virgulino; his proper name was Virgulino Ferreira da Silva.

Lampião began his life as a leather worker. Somehow, at the age of twenty-five, he got in trouble with the law. The police raided his home. In the scuffle, his father was shot to death. It was an act Lampião vowed to make the lawmen regret. And many did. From then until the end of his life, Lampião murdered every policeman he came across.

But, having resolved to be a bandit, he didn’t target only policemen. He robbed old women in their beds. He participated in mass rapes. He cut out the tongue of a woman who’d informed on him. And he removed a man’s eyeballs with a knife just because it amused him to do so. He plundered, and terrorized, and tortured. He was a cold-blooded killer, and a high price was put on his head.

And yet, that’s not the way most young Brazilians see him. To them, he’s a Robin Hood figure, a guy who robbed the rich to help the poor. How did the transformation from repugnant thug to venerated folk hero come about? Partly, I think, because the region he operated in had long been ruled by a few powerful families. The popular psyche called out for an anti-establishment figure – and Lampião filled the bill. Partly, too, because his story contains a modicum of romance. He and his girlfriend robbed together, killed together, had a child together and died together. Here she is, the woman all Brazilians know as Maria Bonita (Pretty Mary).

The couple’s reputation grew with a form of entertainment very popular at the time: “cord literature”, so-called because it was displayed hanging from cords stretched across the front of booths in street markets. The stories were illustrated with woodcuts.

They were often written in rhyme, often set to music.

Later, those early stories gave rise to TV programs and feature films which took a sympathetic view of Lampião and his gang.

(And invariably infuriated my father-in-law, and dear friend, Joel de Britto, who knew, from personal experience, what kind of people Lampião and his girlfriend really were.)

The end for the couple came on a beautiful morning in July of 1938. Here’s the place where it happened, the Grota de Angico, a hideout which, until then, the bandits always considered to be their safest one of all.

The heads were displayed throughout the country before winding up at the Nina Rodrigues Museum in Salvador , Bahia , where they remained on display for almost thirty years.

This final photo is of the youngest member of Lampião’s gang, Antonio Alves de Souza, nicknamed Volta Seca (It means something like “the return of drought”). He was taken alive and sentenced to 145 years in prison, but pardoned after having served only twenty. He took a job as a railway brakeman (that’s the uniform he’s wearing in the photo) married, and had seven children.

There is a song associated with Lampião that almost every Brazilian knows. The gang used to sing it when they rode in to plunder a town. It’s called “Mulher Rendeira” (The Lacemaker) and, some years before his death, someone got Volta Seca to record it. You can listen to it here.

2 comments:

Chilling, Leighton, but fascinating. I've often wondered at the sometimes monstrous people who become folk heroes. What is it about a pair of murderers who rob, torture, and rape that inspires that kind of hero-worship?

And now you've given me an idea for a story. Thank you.

Um ótimo texto obrigado

Post a Comment